Why empathy matters – and how we can do it better

On the first day of my master’s in Counselling & Psychotherapy I was introduced to Carl Rogers ‘core conditions’, in which empathy is key. As a scientist, filmmaker and trainee therapist, my curiosity got the better of me and I wanted to know, what exactly is empathy – what happens in the brain when we feel it, and can learning more about it actually make me a better therapist?

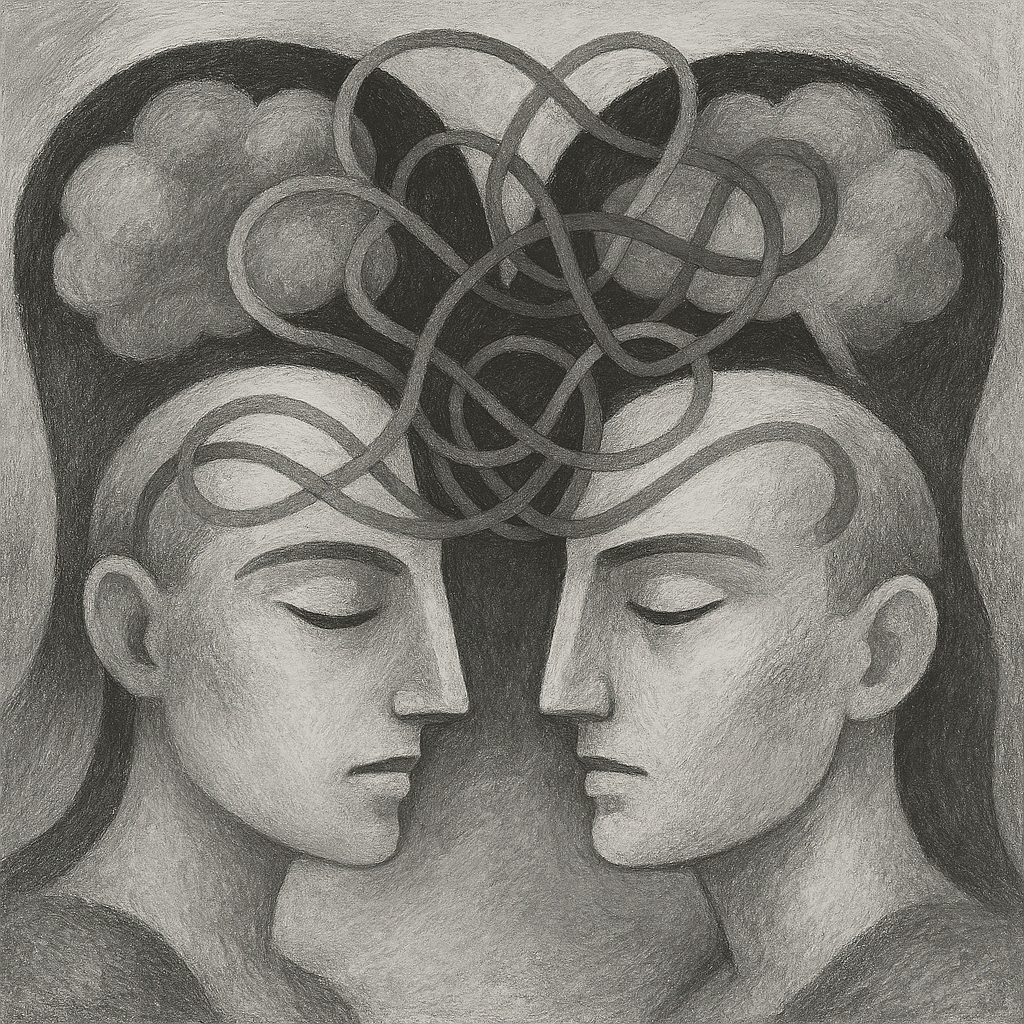

Empathy – more than a feeling

Two kinds of empathy – and why the difference matters

The first thing I discovered is that there are two types of empathy. There’s everyday empathy – the social, human sense we get that another person is feeling sad or joyful – and then there’s therapeutic empathy, which is deeper and more purposeful. In therapy, empathy means stepping into the client’s frame of reference: trying, as far as we can, to see the world through their eyes. The goal is not to fix or tell them what to do, but to help them feel understood so they can trust their own judgement and, potentially, grow.

My film work taught me how to listen for subtext – watching interviews again and again in the edit to find the emotional truth. Therapy is similar, except it happens in real time. The best moments are when time drops away, and the client and I share a common language of feeling, a connection beyond words.

What’s going on in the brain?

Emotional (affective) empathy lights up parts of the brain involved in sensing others’ feelings – regions that help us notice and respond to someone in pain. There’s also cognitive empathy, which is more like perspective-taking – understanding someone’s thoughts without necessarily feeling them. Both are vital for survival, but in the safe environment of the therapy room we mostly rely on affective empathy, coupled with the intention to help. This intention is paramount as it transforms empathy into compassion.

The pitfalls: too much of a good thing

Empathy can be demanding. If we absorb someone else’s distress fully, our own distress can rise to the point where we shut down – and then we can’t help. That’s why therapists need to maintain something Rogers referred to as, “one foot out”: deeply present, but aware that the feelings aren’t ours to carry. Professional boundaries, supervision, and self-care aren’t just niceties – they are central to helping us stay present for others.

Compassion – the skill we should train

As mentioned above, compassion is empathy plus intention: we feel for someone and want to help. The great news is compassion can be trained. Simple practices – mindfulness, self-compassion exercises, and structured compassion training used in healthcare – improve resilience and protect against burnout. For trainees especially, building self-care skills early feels like it would be a huge win.

What about AI?

There’a been a lot in the news recently about the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) being used by people as pocket therapists. My impression is that this use of AI as therapist is partly born of a lack of understanding of what therapy is – how much it relies on the human to human contact underpinning the therapeutic relationship. So, while tools like AI can help with data handling, scheduling or training scenarios, for now the uniquely human capacity to tune into another person’s inner life remains central to person-centred therapy.

Takeaway

Empathy is a powerful skill that can be deepened and shaped. If we learn how it works, practice compassion intentionally, and protect our own wellbeing, we become better therapists – and potentially better humans. I’m still learning, and I’ll keep using film, neuroscience and reflective practice to get there.