The Gift of Normal

Normal often seems to be used as a slightly derogatory term – the beige of adjectives. It’s a word that can flatten things, a way of describing something while quietly implying underwhelm: a normal day, a normal film, a normal person, a normal outfit. Normal can sound like the absence of colour or spark. I think normality deserves a rebrand – a shout out. Because normal, in all its quiet steadiness, is the fabulous peak of the bell curve of life, the perfect temperature for the porridge of experience.

A person walks towards a sunrise.

Normality is a gift we don’t notice until it’s gone. When life has been dominated by anxiety, trauma, or addiction, the ordinary can feel like an extraordinary state of grace. It’s the ability to notice the sunrise as you dress unaided, to watch the news without being overwhelmed, to walk through a supermarket without panic, or to deal with the day’s demands without feeling crushed.

In counselling, amongst the vast array of emotions and experiences people can bring with them, there can be a deep yearning for something that might be called normal. A normal job. A normal relationship. A normal way to feel or to think. A normal relationship with food, alcohol, work, or family. It’s the desire not for fireworks, but for footing – the kind of emotional equilibrium where one can breathe easily, where the days have rhythm and the nights bring rest.

Normal doesn’t mean unfeeling or static – it means regulated, connected, and present. It’s the nervous system at rest. It’s the point at which our emotional weather clears enough for us to see the world and ourselves more fully.

In therapy, as in life, I’m not sure many of us are looking for much more than the peace of feeling “normal” again. And that peace can be hard-won. I’ve also learned that normal is not a static destination. It shifts, grows, and flexes as we do. What feels normal after heartbreak is different from what feels normal after recovery. The landscape changes, but the longing remains – to live in a world that feels safe enough to simply be.

So here’s to normal – to the return of appetite, sleep, connection, laughter. To the gentle pulse of routine. To being able to say, without irony, “It’s been a normal day,” and mean it as the quiet triumph it really is.

Lessons from Documentary Filmmaking that Shaped Me as a Counsellor & Psychotherapist

Before training as a counsellor, I spent many years as a documentary filmmaker, seeking out and then listening to people’s stories, often during times of great vulnerability. I didn’t realise it at the time, but that work was preparing me for the counselling room. The skills I honed behind the camera – curiosity, empathy, and the art of creating safety – have become the foundations of my practice as a person-centred counsellor.

Listening. It sounds so simple. But often when we think we’re listening, we can be thinking about what we’d like to say next. Good documentary work begins with deep listening. To really hear what someone has to say, I needed to be fully present, tuning in to not just what was being said but also the tone, rhythm, pauses – the unspoken as much as the spoken. As a counsellor, that same attentive listening creates a sense a space and acceptance where people can begin to truly hear themselves.

Body Language, the silent language of the mind. When filming interviews, I learned that people communicate more through their bodies than their words – facial expressions, gestures, posture, eye contact… It could be the way a person breathes or their tone of voice. These subtle physical cues can tell a story. In therapy, being sensitive to these cues helps me sense and develop and overall picture of what’s happening beneath the surface, enabling a deeper level of empathy.

From filmmaker to therapist

Making People Feel Safe. In front of a camera, no one is going to just open up and tell you their deepest fears without you doing the work to help them feel safe. The same is true in counselling – how I carry myself matters. Whether it’s through my own body language, tone/volume of voice, or the pace of the conversation, creating a sense of safety is the foundation of an effective therapeutic meeting. It’s what allows both interviewees and clients to be real, open.

Storytelling. Documentary filmmaking is, at its heart, storytelling – finding and revealing the thread of meaning in another's lived experience. Therapy, too, is a storytelling process. Together, counsellor and client work together to explore how life events have contributed to their own narrative, and potentially how we can build on their story to help them shift toward greater self-acceptance and/or personal growth.

Patience and Presence. In documentary filmmaking, you learn that the most authentic moments can’t be forced. They arrive spontaneously, quietly, without pushing. In counselling, this openness to ‘not forcing’ is especially vital – change unfolds in its own time. My role is simply to hold the space, to stay present and patient, allowing the possibility of something new to emerge.

Editing and Perspective. Meaning in film often emerges during the edit, when I have time to watch, rewatch and consider the deeper meanings of what’s in front of me and how it might connect to other aspects of a person’s story – how moments are linked, what’s left out, what’s reframed. Therapy feels like it has a similar rhythm for me – but in real time as client and therapist can work together to “edit” or reevaluate their story, finding compassion and opportunities in the process of retelling.

Ethical Responsibility and Trust. Working with people’s lives on film requires deep ethical care – to represent them truthfully and respectfully. In counselling, that responsibility deepens: I hold people’s stories in complete confidence, honouring the trust they place in me.

Collaboration, Not Control. The best documentaries are co-created – a dynamic partnership between filmmaker and participant. Therapy, too, is a shared journey. I may hold the space, but the client leads the way and together we discover new meaning.

Both documentary filmmaking and counselling are about witnessing humanity in all its messy and beautiful glory – seeing and being seen. The camera taught me to look with empathy; counselling has taught me to listen with it. Both invite the same question: what does it mean to be fully, courageously human?

Vincent van Gogh’s legacy and the need to discuss suicide in the counselling room

Walking around the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, I took the rare step of using their audio guide to help me grasp the immense amount of work this incredible artist left to the world. It was a terrific guide, adding even more colour and texture to the exhibition. And one thing it didn’t shy away from was van Gogh’s mental health. By the end of the exhibition, I was moved to tears at his life and loss.

Almost everyone who’s heard of van Gogh, knows he cut off one of his ears – it’s almost become an unfortunate shorthand for summing up his extraordinary contribution to the world. During a visit in 1888 from his friend and fellow artist, Paul Gaugain, the two strong-willed pioneers argued. After being threatened with a razor, Gaugain left and van Gogh had a mental health crisis, resulting in the removal of his left ear. Less than a month later, Vincent feared his mental health was again deteriorating and he voluntarily admitted himself to Saint-Paul-de-Mausole psychiatric hospital in Saint-Rémy.

Sunflowers, Vincent van Gogh (1888, Public Domain)

While there, he created 150 paintings, not as a consequence of his mental suffering but in spite of it.

This story of van Gogh’s ear is so embedded in stories of his life that it had, until my visit, overshadowed the circumstances surrounding his death. In July, 1890, van Gogh ended his own life and died with his brother by his side.

I found myself profoundly moved by his life, his struggles and his untimely death at just 37. It was impossible to ignore the oxymoron of such a historically troubled life while standing in this vast monument to Vincent’s legacy, filled with people deeply engaged in his work.

“Fear is the only thing in the world that gets smaller as you run towards it.”

In 2023, the most recently published UK-wide official record of confirmed suicides revealed more than 7,000 people died by suicide. And yet, despite these shocking numbers, in day-to-day life we are uncomfortable, possibly even fearful, of discussing suicide and suicide ideation. In the counselling space, it’s entirely different.

In training, we discovered that sometimes a person might directly mention they have thought about or are considering ending their life. Alternatively, they may use language that subtly hints at it. Rather than ignore these cues, a counsellor is encouraged to lean in – if we suspect a person might be considering ending their life, we ask them, it’s that simple.

Van Gogh’s work lives on and we honour his legacy not only by admiring his paintings, but by learning more about the pain he endured in his life. Talking openly about suicide, whether as counsellors or as friends, can be an act of compassion and connection. If you or someone you know is struggling with thoughts of suicide, you’re not alone. In the UK, Samaritans offer free, confidential support 24/7 on 116 123.

Further Support:

Mind Support Line 0300 102 1234

Papyrus Hopeline 0800 068 41 41

Why empathy matters – and how we can do it better

On the first day of my master’s in Counselling & Psychotherapy I was introduced to Carl Rogers ‘core conditions’, in which empathy is key. As a scientist, filmmaker and trainee therapist, my curiosity got the better of me and I wanted to know, what exactly is empathy – what happens in the brain when we feel it, and can learning more about it actually make me a better therapist?

Empathy – more than a feeling

Two kinds of empathy – and why the difference matters

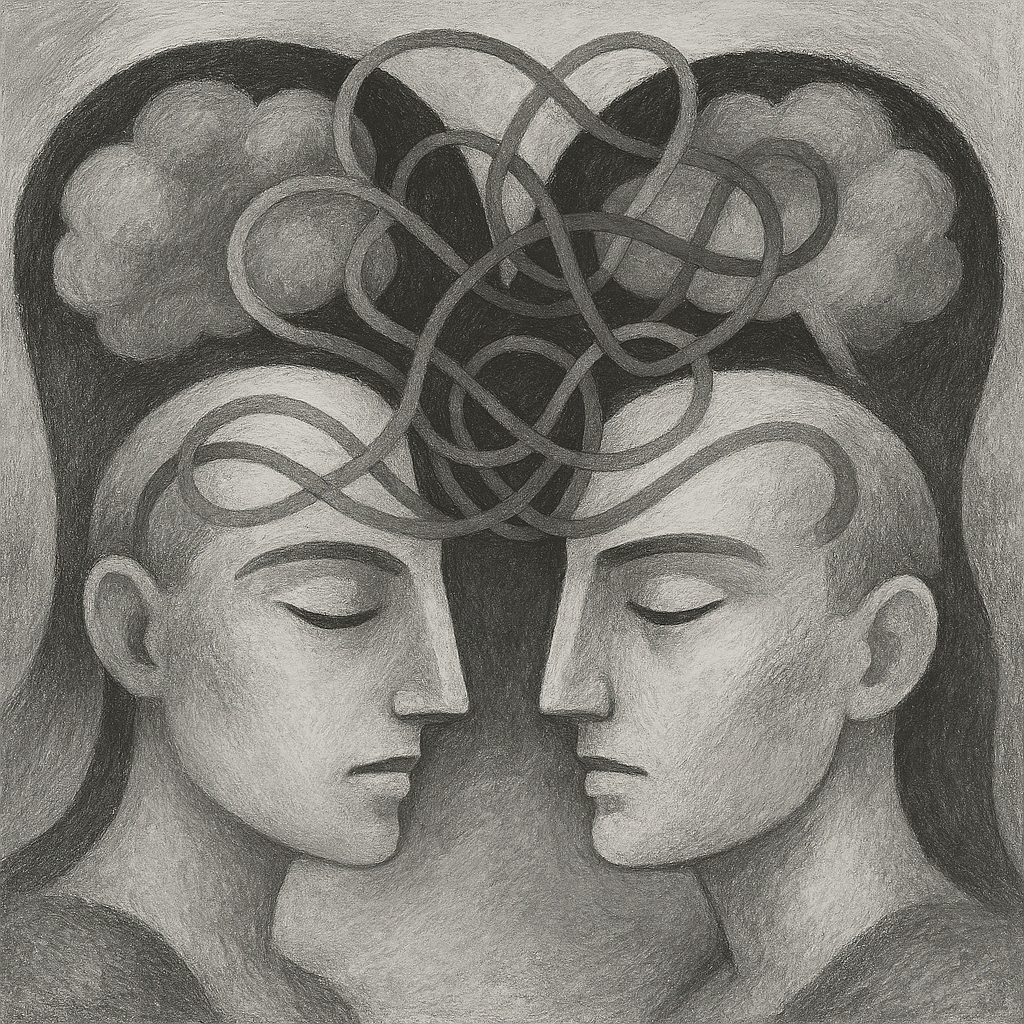

The first thing I discovered is that there are two types of empathy. There’s everyday empathy – the social, human sense we get that another person is feeling sad or joyful – and then there’s therapeutic empathy, which is deeper and more purposeful. In therapy, empathy means stepping into the client’s frame of reference: trying, as far as we can, to see the world through their eyes. The goal is not to fix or tell them what to do, but to help them feel understood so they can trust their own judgement and, potentially, grow.

My film work taught me how to listen for subtext – watching interviews again and again in the edit to find the emotional truth. Therapy is similar, except it happens in real time. The best moments are when time drops away, and the client and I share a common language of feeling, a connection beyond words.

What’s going on in the brain?

Emotional (affective) empathy lights up parts of the brain involved in sensing others’ feelings – regions that help us notice and respond to someone in pain. There’s also cognitive empathy, which is more like perspective-taking – understanding someone’s thoughts without necessarily feeling them. Both are vital for survival, but in the safe environment of the therapy room we mostly rely on affective empathy, coupled with the intention to help. This intention is paramount as it transforms empathy into compassion.

The pitfalls: too much of a good thing

Empathy can be demanding. If we absorb someone else’s distress fully, our own distress can rise to the point where we shut down – and then we can’t help. That’s why therapists need to maintain something Rogers referred to as, “one foot out”: deeply present, but aware that the feelings aren’t ours to carry. Professional boundaries, supervision, and self-care aren’t just niceties – they are central to helping us stay present for others.

Compassion – the skill we should train

As mentioned above, compassion is empathy plus intention: we feel for someone and want to help. The great news is compassion can be trained. Simple practices – mindfulness, self-compassion exercises, and structured compassion training used in healthcare – improve resilience and protect against burnout. For trainees especially, building self-care skills early feels like it would be a huge win.

What about AI?

There’a been a lot in the news recently about the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) being used by people as pocket therapists. My impression is that this use of AI as therapist is partly born of a lack of understanding of what therapy is – how much it relies on the human to human contact underpinning the therapeutic relationship. So, while tools like AI can help with data handling, scheduling or training scenarios, for now the uniquely human capacity to tune into another person’s inner life remains central to person-centred therapy.

Takeaway

Empathy is a powerful skill that can be deepened and shaped. If we learn how it works, practice compassion intentionally, and protect our own wellbeing, we become better therapists – and potentially better humans. I’m still learning, and I’ll keep using film, neuroscience and reflective practice to get there.

Grief, the human experience uniting us all

I’m finding it hard to watch the news these days and I doubt I’m alone. War seems to have become an Orwellian hellscape, with drones exploding, genocide looming and the far right becoming more vocal as the truth becomes owned by those who shout loudest. It can feel, some days, as if humankind actively seeks methods to divide itself into ever smaller, more righteous, zealous or political categories.

But this week I experienced a glimmer of hope – and it came in the unlikely form of grieving for my younger sister, who died one year ago this week. A hospice local to me, Compton Care, had a sponsored walk in which we raised money to support those who need it while taking advantage of the beautiful nature walk along the canal to contemplate those we’ve loved and lost.

All of life was there. It was sad, happy, thoughtful, friendly and supportive as our crowd of hundreds walked together, remembering spouses, parents and siblings. And it was wonderfully diverse, a beautiful reminder of how humane humanity is and can be. As we strolled, I was just as moved by the experience in the moment as by the memories that arose.

It was a powerful reminder that grief, and death, unites us all.

“When the other person is hurting, confused, troubled, anxious, alienated, terrified; or when he or she is doubtful of self-worth, uncertain as to identity – then understanding is called for. The gentle and sensitive companionship offered by an empathic person… provides illumination and healing. In such situations deep understanding is, I believe, the most precious gift one can give to another.”

In counselling and psychotherapy, how to work with bereavement inevitably forms part of a counsellor’s training landscape. But even as I write that it sounds odd, as if working with grief is a bit like tackling a leaky boiler. The truth is, there is no set way to work with grief when you’re a person-centred counsellor – what there is, is a way of being fully with a person, within their utterly unique experience of their grief as an accepting and empathic presence.

I suspect many of us have fallen for the most common myths around grief (I know I had). It’s just so tempting to think that if we ignore it, it will quickly pass or that even if we can turn our gaze towards it, then it’ll probably be over within a year. Neither of these common beliefs are true.

My sister died just days into my training. Immediately, life made no sense – I had no idea whether I could continue the training, how her tragic and unexpected death would impact me, my family. What kept me going were two things. The first was our last conversation in which my sister called me to tell me how proud she was that I was training to “help people like her”, by which she meant anyone who was struggling with their mental wellbeing.

The second thing that propelled me through was the training itself. An integral part of our training involved counselling fellow classmates – not with imagined scenarios but our real lives. Suddenly, I was in the midst of my grief but also in the midst of around 100 other trainee counsellors with whom, over a period of months, I openly wept, voiced my frustrations and disbelief. The regrets.

Today, I can mostly remember my sister with a smile, but it’s also okay to cry gently too – I am only, wonderfully, human.

What is counselling and do you need it?

It all begins with an idea.

When I first went to therapy, I was anxious, convinced I didn’t need it. Sure, life had been hard for the last year or so but therapy? Growing up in a working-class household in Scotland, therapy was something Americans and aristocrats did. As the weeks with my therapist went by, however, I found myself relaxing, unfolding, sharing aspects of myself and my past I had never told a soul. I laughed, cried and ultimately felt a profound weight I hadn’t even realised I’d been carrying fall away from me, leaving me lighter, happier and able to navigate life more easily.

I am a counsellor. As part of my master’s degree in counselling and psychotherapy training at Keele University, I had no choice but to undergo therapy. The impact was so profound that my entire dissertation became about my personal journey. It also left me with an unequivocal conviction that therapy can benefit everyone.

So, is it right for you? There’s a whole raft of reasons someone might end up in a chair with a therapist – the loss of a loved one, crippling anxiety, low self-esteem, depression, and so on. But it can also be hard to pin a specific reason down. While I wasn’t aware of the need for therapy, I can look back now and see that life had colluded to leave me withered. Shortly after a diagnosis of severe arthritis, I was living with chronic pain. Then my father died of vascular dementia – a cruel demise. One day I just couldn’t see a way forward, there was no sense of happiness on the horizon. This is how it can start, a sense of feeling something is wrong even though you can’t clearly articulate it.

The world of counselling is full of modalities, different specialties – I’m a person-centred therapist. What does that mean? Imagine going for a walk with someone who lets you lead the way, listens carefully to whatever you wish to discuss, without interruption, without judgement. Every now and then they may make an observation, and it feels like they really get you, that they genuinely understand. They won’t tell you how or what to think, instead they allow you – possibly for the first time – to fully, safely explore your own thoughts, perceptions and experiences.

It sounds simple but over time, this approach can be transformational, leading to greater self-awareness, self-acceptance, and the confidence to make changes. At the heart of the person-centred approach is the immense body of work from renowned psychologist, Carl Rogers. He believed ever person has within them the desire and the ability to grow – but sometimes this capacity for growth is thwarted or blocked by life. Working together with a therapist can help to remove such blockages.

At Serenity, we have a broad and experienced team of counsellors, each with their own areas of expertise. No matter what you’re struggling with, someone here will be able to meet you with compassion, understanding, and skill. If you’re reading this and wondering whether counselling could help, it’s okay to reach out. We know that taking that first step requires courage – it also means you’re ready to explore a different way forward. At Serenity, we’ll be here to walk alongside you as you navigate your own path towards clarity, healing, and hope.